Milton Friedman used to advise researchers to focus on large policy changes rather than attempting to separate a small change’s signal from the noise. In this sense, the “ambitious” policy agenda of the Biden-Harris administration was expected to be a gift to the research community.

Accepting this gift, since 2020 I have been making forecasts of some of the consequences of those policies. Now is a good time to assess the accuracy of those forecasts, which relate to aggregate labor markets, insurance price controls, and drug price controls.

As promised, Biden and Harris redistribute income with health insurance expansions and student-loan forgiveness, although not necessarily in the Robin Hood direction. They give union bosses more tools for reducing competition in the labor market. They try to regulate the internet as a public utility. They distort healthcare markets in many ways, including a new ban on short-term health insurance plans, and granting selected companies a monopoly on a generic drug. They go significantly further than the Obama administration in terms of requiring the private sector to change behavior in ways the bureaucrats expect to reduce carbon emissions. At great human-capital expense, they enabled teacher unions and blue-state governments to maintain “social distancing” far longer than warranted.

The exhaustive list would have more than 1,000 entries. Overall, even the federal agencies’ own low-ball estimates of the costs of the regulations finalized 2021-24 are almost $2 trillion.

1. Macro Performance

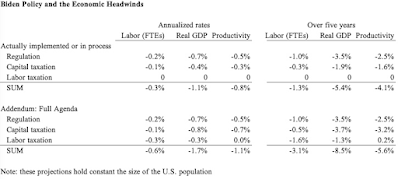

Four years ago, I released a study with Kevin Hassett, Tim Fitzgerald, and Cody Kallen of the economic effects of candidate Biden’s agenda compared to President Trump’s. Knowing that campaign promises do not necessarily turn into policy, we analyzed several policy scenarios. The scenario closest to the portfolio of policy changes over the past four years we called “capital taxation constant” (CTC). Biden-Harris climate regulations proved to be somewhat more aggressive than represented by the CTC scenario including, for example, a requirement that manufacturers of medical inhalers (sic) either cease production or convince the Environmental Protection Agency that they are earnestly seeking lower-emission technologies. On the other hand, as nonlawyers we did not account for such a high failure rate of Biden-Harris rules in federal courts.

Under the CTC scenario, labor and capital would be 5.0 percent below the Trump baseline in the long run. In tomorrow's Wall Street Journal, we show that a single trend fits the data well from 2017-Q1 through 2021-Q4, except for the first full pandemic quarter. Then inflation hit and employee compensation—and national income more broadly, which isn’t shown in the chart—fell 5 percent behind. To be more precise, the latest data (2024-Q2) show inflation-adjusted employee compensation per adult to be 4.6 percent below the trend.

We used a closed-economy model (tariffs were modeled like other excise taxes) that imposes a constant labor’s share, a constant depreciation rate, no statistical discrepancy, and equality between GNP and GDP. In reality, labor’s share of national income has been pretty constant, but the national income’s share of GNP has fallen a bit. More significant has been a fall in the ratio of GNP to GDP. Conversely, a real GDP per capita chart would look “better” than our compensation chart, which of course is no consolation for workers.