From July 2018 to June 2019, I served as Chief Economist of the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA). My primary responsibilities were preparing public reports, supervising senior economists and interacting with various groups in the White House and in the relevant agencies on a wide range of topics.

As CEA engaged in topics, they were picked up by Kevin Hassett (especially tax and trade), Tom Philipson (esp. health, infrastructure, student loans), Rich Burkhauser (esp. labor, immigration, and social programs), or me (Affordable Care Act, socialism, regulation, wage growth, macro aspects of trade).

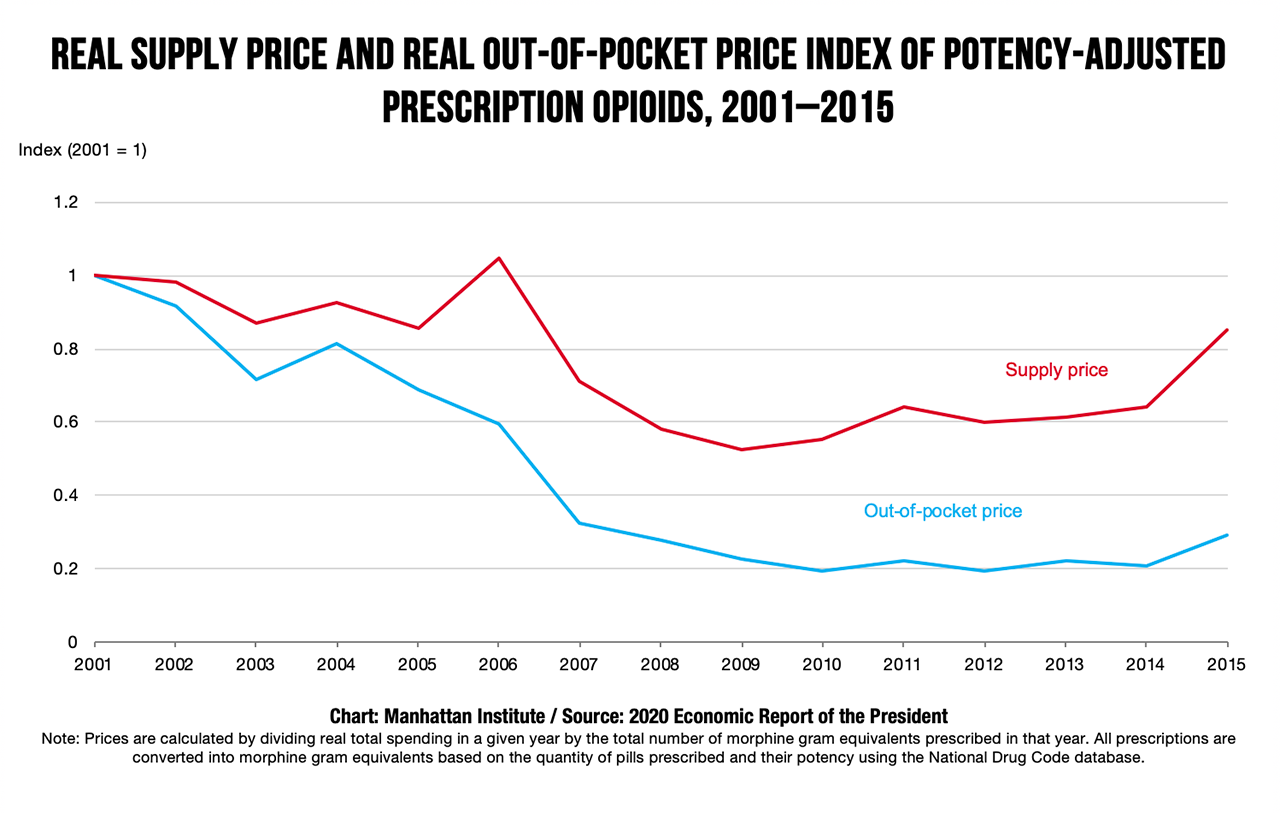

On some of the topics I worked serially or in tandem with Tom (health insurance regulation, Medicare Part D, the Rx CPI, opioid prices) and in tandem with Rich (

TROIKA).

The large majority of my time was in various stages of preparing Administration reports for the public, most of which were CEA products although OMB publishes the TROIKA results and the agencies publish rulemaking documents (which CEA sometimes edits).

Typical activities: Supply and Demand

The pace and daily execution of my work closely resembled academic research and economics consulting in litigation matters. This is probably unusual in the history of the CEA, but was the result of three practices:

- anticipating the needs of POTUS and EOP economic principals,

- fitting questions into the catalog of economic theory so that established methods and literatures could be used to quickly obtain reliable answers, and

- using already-published CEA reports to facilitate accurate and consistent execution of new tasks.

Much public policy discussion is devoid of economics and thereby obscures evaluation of current Federal policies.

Invariably these were policy areas where EOP principals most valued CEA’s work.

Socialism and Medicare for All (see also their updates in the in

2019 Economic Report of the President) are good examples where CEA was able to initiate or at least bend the conversation by assembling results from economic research.

Probably the best tool is the empirical counterpart of the supply and demand picture.

That is, measuring both price and quantity using the best methods available in the academic literature.

CEA is desperately needed to perform this function.

The current CEA already has 11 instances of those pictures in its

Economic Reports of the President, as compared to only 8 for all of the combined other Presidential Administrations in U.S. history.

This may seem to be a trivial enterprise, but the “best” in our profession fail at it regularly (see below and

here and

here).

Prescription drugs are another important example.

The typical narrative (including at HHS,

which sees itself as the drug-price regulator) was that prescription drug prices were increasing faster than general inflation, as they had for decades. But, with attention to the institutional details of the supply chain, CEA found that the best measures showed an increase in quantities of prescriptions at the same time that prices have been falling over the past two years or so.

CEA’s trade team executed these methods repeatedly as various tariff rates were changed.

One Economics

I looked carefully and critically at the headline calculations of all CEA reports released during the year (beyond the 12 reports or ERP sections that I edited), as well as the

corporate tax reports released at the end of 2017.

The essential methods and sources for these calculations proved to be consistent across reports including, but not limited to, tax, immigration, health, socialism, and regulation.

A three-good version of the neoclassical growth model with taxes was another workhorse that links industry-specific analysis with macroeconomic analysis.

The three goods are leisure and two consumption goods (but see below).

CEA used that to look at Medicare for All (health consumption vs other consumption), tariffs (tariffed goods vs other goods), and dozens of regulations (regulated good vs other consumption goods). We also used it to look at business tax reform and investment regulation, where there is just

one consumption good but two capital goods (

corporate vs noncorporate).

We typically focused on the steady state and took a broad view of “taxation” that encompasses other market distortions.

We derived quantitative rules of thumb (such as the well-known marginal excess burden of taxation) for the effects of a single sector’s distortion on the aggregate supplies of labor and capital.

Working in a Large Organization

The Executive Office of the President (EOP, of which CEA is one of several components), not to mention the entire Federal government, is a large organization with components far more inter-reliant than the components of a university. Professors joining CEA need to be aware that staff meetings are critical for keeping information flowing to the parts of the EOP that need it. As you attend EOP meetings in your subject area, be prepared to share headlines with the rest of the CEA staff at the staff meetings and listen to others to assess who in CEA or outside CEA might be of help for the next task that arrives.

The EOP has a staff hierarchy for the same reasons, although many employees adhere to it so rigidly that there is a role for organizational entrepreneurs who cross some of those boundaries, which is a role I took on in much of my work.

Otherwise meetings of principals (a.k.a., cabinet-level positions) and deputies (report directly to principals) may not have anyone present who knows first hand the details of the meetings’ subject.

I presume that this is also a problem in large private organizations, but more acute in government where leaks are more of a constraint on determining who is invited to meetings (see, e.g.,

this memoir’s discussion of leaks in the Obama White House).

CEA Chairman Hassett and COS DJ Nordquist assembled an amazing team of economists. I also worked closely with six other components of the Federal government: the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the National Economic Council (NEC), the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA, technically part of OMB), the Domestic Policy Council (DPC), the Department of Labor (DOL), and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Every day working in the EOP was a pleasure (Mick Mulvaney = Phil Jackson; the Kelly-Collins analogy is imperfect). It is difficult saying goodbye to so many excellent EOP colleagues but by design CEA has high turnover so that others outside can come in with fresh ideas and energy.

[In returning to the University of Chicago, I return to publishing under my own name and take sole responsibility for the analysis and conclusions. As such, the Federal government is not consulted on my writings.]