Treasury Secretary Yellen does not see any indicator of an imminent recession. She isn’t looking. The normal economic tailwinds have calmed and, as predicted, Biden's economic policies are a significant headwind.

A recession is sometimes defined as a reduction in the number employed nationally for a couple of months. Other times it is defined as a reduction in real GDP for two quarters or more.

When it comes to predicting events like this, my recursive approach is to first understand where the general trends are heading. In technical terms, is the economy’s “steady state” above or below where we are now, and how much? If the trends are strong up, small perturbations around that trend will not make a recession. If the trends are flat, then even a small negative shock will create a recession by one or more of the definitions. Which definition will be triggered can be assessed by contrasting employment trends with productivity trends.

Four important trends are worth considering: organic productivity growth, organic population growth, recovery from the pandemic recession, and new public policies affecting productivity, population, or employment.

Organic trends

Given that recessions are defined in absolute rather than per capita terms, population growth is normally an economic tailwind. However, annual adult population has fallen from a bit above one percent 1980-2018 to about 0.4 percent. Illegal immigration is a wild card here because we do not know how many are immigrating, what fraction are adults, and whether and how those adults will be economically engaged. With that caveat, we now are in a situation where even a small negative shock that would not have caused a recession in the one-percent population growth era will now.

Recovery from the pandemic was also a tailwind. It someday will continue to lift employment, but at the moment it looks like employment has recovered as much as it can given the serious health problems encountered during the pandemic, including but not limited to self-destructive substance abuse habits that are not complementary with productive employment. Some of these people will show up on payrolls but how reliably they show up for work is another question. Diabetes, liver disease and heart disease have gotten out of control since 2020.

Workers lost skills and capital laid idle during the pandemic. These are recovering, although their recovery will not be fully recognized in the growth data. GDP and productivity levels were exaggerated during the pandemic as many goods were unavailable or low quality in ways not captured by the national accountants. For example, public school teachers stayed home from school but the national accountants assumed that they were as productive as ever merely because they continued to get paid. As they get back to traditional teaching, this will not be officially recognized as economic progress for the same reason the pandemic regress was never acknowledged.

Crime has gotten bad, especially in big cities where productivity is normally the highest. Consumers and businesses are avoiding big cities, which is a cost (“excess burden”) beyond the crime statistics because the whole point of the avoidance behaviors is to keep from being one of those statistics.

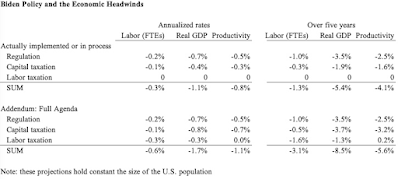

Fitzgerald, Hassett, and I predicted in 2020 that Biden’s economic agenda would reduce the levels of full-time equivalent employment per capita by 3.1 percent and real gdp per capita by 8.5 percent. If that level effect were spread over five years, that would be 0.6 percent per year and 1.7 percent per year, respectively, as shown in the Table as an addendum panel. That by itself makes a recession likely in one of those five years.

Regulatory Policy

Our analysis of Biden’s agenda distinguished regulation from capital taxation from labor taxation. His regulatory agenda seems to be going ahead as we expected. The good news is that Biden’s nomination of David Weil to the Department of Labor was rejected by the Senate and Biden was slow to fully mismanage the National Labor Relations Board. But we did not anticipate that Biden’s DOL would disrupt labor markets as much as it did with its mask mandates. Sticking with our original estimate, it looks that Biden’s regulatory agenda is reducing employment by 0.2 percent per year (of five years) and real GDP by 0.7 percent per year below the organic trends. See the Table’s top panel.

Of particular concern over the next few months is the reliability of the electric grid and air travel. Snafus of this type are already built into our regulatory analysis but these examples put more texture on the economic reasoning that links the marginal regulations with poor economic performance.

Capital Taxation: Inflation Sneaks In

Biden’s Build Back Better bill would implement much of the capital taxation we envisioned in 2020. The good news is that the bill has not yet passed, and passage of its capital tax elements are not imminent in some other form. The bad news is that inflation is taxing businesses without any Congressional action (recall Feldstein and more recently Hassett on the effect of inflation on the cost of capital), while it appears that Biden will let temporary provisions in the 2017 TCJA expire. With capital taxation during the Biden administration increasing about half of what we expected, it would reduce real GDP by about 0.4 percent per year over five years.

Speaking of inflation, higher Fed Funds rates are already showing up in mortgage rates. In effect, the Federal Reserve is introducing a tax (or cutting a subsidy) on structures investment, which is likely to send at least that sector into a recession. Socially responsible (a.k.a., woke) investing is also skewing the allocation of capital.

Combining capital taxation and regulation, the headwinds in the Biden economy are 0.25 percent per year for employment and 1.1 percent per year for real GDP.

Labor Taxation: Direction Unclear

Labor taxation is an interesting wild card here. Marginal tax rates on work were cut sharply when the $300 weekly unemployment bonus expired last summer. That effect has played out already. But I expect that Congressional Democrats, and even some Republicans, will expand unemployment benefits if anything resembling a recession were occurring. That could easily and quickly reduce employment by one percent, if not more. On the other hand, various federal health insurance subsidies are about to expire. If they do (without resurrection), that will encourage work.

Bottom Line

Overall, a recession is highly likely with so many headwinds and so few tailwinds. A recession is more likely by the GDP definition than the employment definition. The depth of the recession depends on how much Congress destabilizes things by further adding to the already large federal portfolio of programs for the unemployed and poor and further adding to tax burdens.

1 comment:

Atlanta Fed's Q2 GDPNow is at 0.0% on June 16, on June 8, it was 1.9% and on June 1 it was 1.4%. Their next report is June 28 and I think it will be -0.6%. The stock and bond markets are reflecting this. What is your expectation of Q2 GDP Dr. Mulligan?

Post a Comment