It appears that the main disagreement between BEA and I is about the inflation/deflation rate. They see -0.3 and I see -3.3.

My nominal GDP prediction was close -- it's just that I saw the GDP deflator falling more. The experts saw the GDP deflator going up.

From 2008 Q3 to 2008Q4, aggregate labor hours fell 7.4% (at an annual rate).

The BEA reported today that aggregate real GDP (that is, aggregate spending) fell only 3.8%.

That means:

Recall that my calculations for 2008 Q4 say -2.2, +0.4, and +0.8 (depending on the method) -- as compared to the -5.4 cited above.

President Barack Obama expressed a vision for federal spending: that 2009 presents an opportunity for the federal government to invest in infrastructure, health care, and education sooner rather than later. Investments like these have intrinsic value — they are appealing because they are believed to serve the greater good — but not much stimulation potential.

When the government hires employees or makes purchases, their ultimate economic effect depends on what private sector activity is displaced.

In one scenario – called “crowding out” in economic jargon – some (but not necessarily all) of the new government employees are people who quit their private sector jobs in order to accept better positions offered by the public sector, and many (but not necessarily all) the new government purchases just take items that would have been purchased by a household or private business.

For example, an improvement of public schools may cause some students to withdraw from private schools and enroll in public ones and cause some school employees to relocate from private to public. The stimulus potential is minimal in this scenario, because much activity is shifting from private to public rather than being recreated anew. Gross domestic product may increase, but less than the public spending does – because public spending “crowds out,” or displaces, private spending.

Many people believe that moving students from private to public schools has intrinsic value. Or that building a public highway has intrinsic value even if it reduces private construction. Or that modernizing health care data has intrinsic value even if it reduces some other activity in technology industry. Thus, government purchases might be desirable even if they are not stimulating.

The second scenario is called the “multiplier.” In this view, government hiring and purchases largely acquire employees and resources that would have otherwise been idle. If this were correct, than the government’s spending in one area would not reduce spending in another. Instead, it would employ otherwise unemployed people, and get them spending again, thereby creating private spending on top of the government spending – hence the term “multiplier”. In the multiplier view, G.D.P. increases more than public spending.

Despite the recent increase in unemployment rates, I see little reason why the multiplier scenario is realistic. For example, President Obama’s economists have explained how about half of the jobs they plan to create (both directly and indirectly) are jobs for women. But the large majority of this recession’s employment reduction has been among men. Thus, the Obama spending plan is not designed to primarily draw on the pool of persons unemployed in this recession.

President Obama has a vision to spend more on health care, largely for its intrinsic value. Its stimulation value is minimal because unemployment is low in that sector; health sector employment has actually increased every single month during this recession.

Even the construction industry shows crowding out. The chart below shows two types of construction spending over time: residential and non-residential. The housing boom prior to 2006 clearly crowded out non-residential construction.

Perhaps there was not enough unemployment during the housing boom to realize the multiplier effect. But in the two-year period since the end of 2006 – the last twelve months of which have been an official recession – shows a similar pattern: Reduced spending in one area allows for more spending in another.

Significant publicity has been given to residential construction workers and equipment that became unemployed since 2006, but less recognized is the absorption of many (but by no means not all) of those resources by non-residential construction projects. Public spending on construction that might come from the President’s spending plan will re-employ so of those unemployed, but it will also draw others out of their current work activity. The latter is why crowding out will occur even in construction.

Government spending will reduce private spending virtually anywhere it may be targeted. The case for government spending should be made on its intrinsic, not stimulation, value.

The productivity forecast is the simplest: I take the -7.4 %/yr decline in aggregate work hours and assume that productivity rises via a movement up the labor demand curve, which yields -5.2%/yr. The pundits appear to stop here, assuming no productivity growth for a given amount of labor. But productivity has been increasing throughout this recession, so why should it stop now?! Thus I get -2.2%/yr.

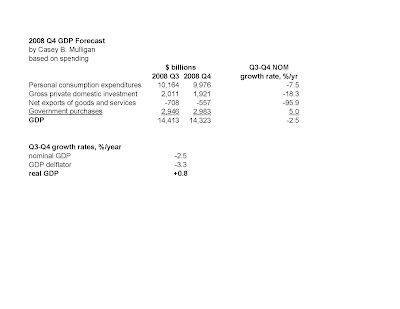

The forecasts based on income and spending are shown in more detail below. In terms of the income account, the fairly strong aggregate payroll spending (as indicated by BEA and by Treasury payroll tax collections) are my reasons for optimism. In terms of the spending account, my optimism comes from net exports and my view that this recession's investment decline will be MILD.

I do not want to exaggerate the degree of precision any of us have -- the gap between my most and least optimistic forecast is only about $75 per person. The gap between Goldman and my least optimistic forecast is also about $75 per person. But there is no doubt that I see Q4 a lot differently than do the pundits.

Note: I have been saying for a while (e.g., here) that real GDP may well grow Q3 - Q4. All that is new today is that I have organized the details well enough to post here.

Professor Cochrane writes "Every job created by stimulus spending is one job not created by the private spending it must displace."

I agree very much that crowding out is real. WWII is a nice example. For a 2008 example, look here or in my post this Wednesday.

But he is wrong to claim that crowding out has to be one for one. Again look at WWII -- yes GDP went up less than government spending, but it still went up. The adverse wealth effect of taxes is one mechanism by which it can happen. An intertemporal substitution effect is another.

Of course, the fact that public spending can increase GDP does not make it desirable! But let's get the positive analysis right.

Professor Cochrane writes "The only thing that matters is new debt, not who takes the hit for old bad debt"

It DOES matter who takes the hit for old debt: if the hit taken is a function of income, then debtors have little (in some cases, zero) incentive to work. I have noted this several times as relates to "mortgage modification" and tax debt forgiveness.

Also note that construction spending (including nonresidential) is higher in Q4 than it was in Q3. How does this happen if savings-investment intermediation is so terribly broken as Cochrane says?

The terrible bottom line of Friday’s job report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (B.L.S.) did not surprise many people – there were many fewer jobs in December 2008 than in the prior month.

Much less noticed, however, was Friday’s breakdown by sex of employment declines prior to December. Is it possible that one legacy of this recession is that women become a majority of the workforce for the first time in American history?

Years ago, women were a small minority of the workforce (outside the home). During much of the twentieth century – especially the 1970s and 1980s – women increased their share. By 1990, the workforce was 47 percent female and 53 percent male, according to the B.L.S. Many view this as one of the most important and desirable social and economic transformations of our lifetimes.

Until this recession, women throughout the 1990s and 2000s remained less than 49 percent of the workforce. However, that percentage has now passed 49 percent and may cross the 50 percent threshold for the first time.

In November 2008, the female workforce shrank more in percentage terms than it ever has in any one month – and more than ever over any single year – since 1964, if not longer. Nevertheless, female workforce reductions so far in this recession are smaller than those for the male workforce – even when measured in percentage terms – as has been the case in previous recessions.

The table below displays calculations for three recessions – 1990-91, 2001, and today. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the recessions began in July 1990, March 2001, and December 2007, respectively. The first two ended in March 1991 and November 2001. Two notes: First, nobody knows when this recession will end, and second, the most recent data for which the B.L.S. reports employment by sex is November 2008.

During the first recession, male employment fell by 2.0 percent, while female employment hardly fell at all (less than 0.05 percent). In the other two recessions, the percentage employment loss for men exceeded that for women by a factor of 3 to 5 (interestingly, although women still have a small minority of each recession’s employment decline, the female share of the decline has increased from one recession to the next, indicating that women’s jobs have become more sensitive to changes in the business cycle).

The bottom of the table shows how, as a result of the larger male jobs losses, recessions have increased women’s percentage of the work force by about 0.5 in recent recessions. For example, the 0.5 percentage point increase that occurred in the eight months of the 1990-91 recession is more than occurred for the ten years that followed, or in the six years that followed the 2001 recession.

If the pundits are right that this recession will be long and severe, then women may gain the 0.9 percentage points from November 2008 that would push them past the 50 percent milestone. Important milestones will remain to be achieved, but women’s surpassing 50 percent of employment is something that historians will note for years to come.

The Federal Reserve Bank of NY has a nice calendar.

The basis for these 3: investment can continue even while banks are in a mess (see my nytimes piece in Oct).

(1) is not a short term prediction, because this basis does not say exactly how long it takes other sectors to absorb former construction and bank employees. (2) and (3) are both short and long term predictions.

If one of these turns out to be wrong, but investment remains strong then we will all be puzzled because it was the banks who were supposed to bring disaster through an investment collapse. But in this case I will admit that I neglected some very fundamental factors.

(4) housing construction will resume my summer 2009.

(4) is based on the combination of my view of the banking system (that it is able to make housing loans as soon as it makes economic sense to build houses) AND my estimate of the pre-"bubble" trend for housing demand. If I were wrong about the latter, then housing construction would resume later for reasons having nothing to do with banks. One way to confirm this interpretation versus others is to look at housing rents -- if they get high then I'll admit that banks are holding back supply.

(5) real GDP may grow Q3-Q4 less than -5 percent (annualized), but it is just as likely to grow more than zero.

(5) is NOT based on my hypotheses about the banking system. It is based on two things: (a) my view that productivity and employment move in opposite directions in this recession (this view has little to do with my view of banking and investment), which makes me a little more optimistic Q3-Q4 than the consensus forecast, and (b) my statistical analysis of October and November (all that I have right now) national income items. Thus, if (5) is wrong, it is because my productivity forecast was wrong or because the December data was dramatically different than Oct-Nov or because the national income accounts' "statistical discrepancy" (an official item) were large relative to the gap between my forecast and others'. The result of (5), and the reasons for it, will be known Jan 30, 2009.

After Lehman failed and “credit markets froze” in the second half of September 2008, many people proclaimed that a second Great Depression would unfold. In hindsight, we readily see that at least one of the purported pathways to depression was never followed.

During the first days of October 2008, it was claimed that businesses would not be able to borrow from banks even for basic operational expenses, such as making their payrolls. As employees had to work without pay (so the story goes), the businesses patronized by those employees would suffer, and the downward spiral would continue. Then presidential-candidate Barack Obama said that “the credit market is seized up and businesses, for instance, can't get loans to meet payroll.” It was even suggested that “recession proof” employers such as colleges and municipalities would not be able to pay their employees.

Now that a couple of months have passed, let’s look at payroll spending measured by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The chart below shows payroll spending (measured in billions of dollars) for each of the months of second half of 2008 (December data not yet available), including contributions to pension and health funds for employees. Aggregate payroll spending was highest in August, and has remained within 0.1 percent of the August high ever since.

The Lehman Brothers investment bank failed on September 15. The bank was deeply intertwined with other financial institutions – its failure to pay its obligations put its creditors at risk – and brought the credit crisis to its crescendo. By the end of the month, the intense financial chaos motivated Mr. Obama and others to warn that banks needed lots of money from taxpayers, or else the banks’ business customers would not be able to pay their employees.

Because the bailout bill took time to pass, and then additional time for the Treasury to design and execute its $700 billion Capital Purchase Program (CPP), no bank received any money from the Treasury pursuant to the CPP until the last couple of days of October. Thus, if the warnings were right, payroll spending should have been precipitously lower in October than in the previous months. Instead, payroll spending was almost $1 billion dollars higher in October than in September – not exactly the collapse that we feared.

Some of the details of the CPP became known earlier in October. Anticipation of the CPP expenditures cannot explain why payroll spending did not collapse in October, because the purported pathway to depression was about the day-to-day cash needs of otherwise strong businesses. Even the United States Treasury admitted last week that “capital [from its CPP] needs to get into the system before it can have the desired effect.”

Even when some (but by no means all) of the CPP funds finally got “into the system” in the last days of October and the full month of November, Congress was dismayed to see that banks were not using the funds to lend. Nevertheless, payroll spending did not collapse in November, either.

It is true that payroll employment fell by about 850,000 in October and November – and that’s serious as compared to the last couple of recessions – but the payroll spending data show that the employment loss was small compared to the spending collapse forecasted in early October. The fact is that more than 136,000,000 workers received their paychecks – more than $1.3 trillion worth in October and November combined – essentially the same aggregate payroll that was paid out in the two months prior to Obama’s warning.

None of the above denies or confirms that our economy is headed for economic depression, because there are multiple pathways for getting there. Nor does it deny that the Treasury CPP might help in some way. But it does refute one of the scariest pathways to Depression – a collapse of payroll spending – that politicians from both parties alarmingly described to the American public in order to justify spending $700 billion of taxpayer funds on a bailout of United States banks.

You might say events have changed significantly since Nov 4, and these events coincidentally caused President-elect Obama to act more Republican. What events, exactly? Are we more worried about the economy now than we were in October (remember that's the month when we decided to give away $700 billion to banks)? Is it brand new that Israel has violent encounters with Hamas?

And why does coincidence perennially push in the directions of causing Democrats to act more Republican and Republicans to act more Democratic?

I really should stop fighting the utter neglect of supply, and instead appreciate its productive value.

A silver lining for banks is perhaps that markets already had anticipated some construction cost declines.

disclusure: long XLF