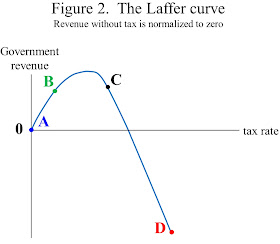

Figure 1 is the familiar chart showing the “Laffer curve” relationship between a tax rate and the net revenue from the tax. A small tax on, say, wireless internet service is expected to provide more revenue (point B) than would be obtained without any tax on wireless internet service (point A). It is conceivable that the wireless internet tax rate could get so high that further increases in the rate actually reduce revenue (point C) as consumers take steps to evade taxation altogether. At point C, economics gets really interesting because many of the difficult public policy marginal tradeoffs disappear.

When it comes to various taxes in the United States, at least, we economists typically expect that the operative point is B. E.g., the Federal payroll tax is probably at a point where further increases in the rate would raise at least some revenue, albeit less than static scores that make little distinction between points A and B.

The statutory Federal corporate rate is an interesting case, especially three years ago when it was well above rates elsewhere in the world. Arguably cutting that rate increased Federal revenue as at point C (combined revenues from payroll, personal income, and corporate income). But other reasonable experts could opine that point B was and is the operative point for the corporate tax rate. And even these opposing experts would likely agree that the operative point (B or C) is above point A where the tax is abolished.

My only point here is that we would be at a unique chapter in economic history if a tax were obviously at point C or beyond. So turn now to Figure 2, especially its point D where the government receives more revenue by abolishing the tax. This was the case with the Affordable Care Act’s tax on uninsurance (a.k.a., individual mandate tax).

(I cannot say for sure how the path evolves between points A and D, e.g., perhaps the path never crosses above the horizontal axis, but that issue is not important for what follows.)

The first chapter of my ACA book explained what was happening, using the story of Pastor Ben Winslett who described how the ACA “has placed an enormous financial burden on normal, everyday people quite literally forcing us onto government assistance we didn’t need before.” In other words, the individual mandate penalized people for turning down government assistance! Mick Mulvaney explains here.

The government saves money by reducing the punishment it imposes on people who turn down subsidies because more people turn down the subsidies.

You don’t have to believe me. Look at Jonathan Gruber’s 2010 analysis of repealing the individual mandate, where he projected (p. 4) that repealing it would reduce Federal spending by about $46 billion per year, while sacrificing much less than that in terms of mandate collections. Or the Congressional Budget Office projection that repealing the mandate would reduce Federal spending by about $34 billion per year, while sacrificing much less than that in terms of mandate collections. I (and the current CEA) think that those two estimates are exaggerated, but if Gruber and CBO stand by their qualitative analysis then all four of us must agree that point D is the operative point.

Having a tax at point D easily makes the highlights of economic history. Neither my book (which focused on the subsidies and the employer mandate), Gruber’s report, nor the CBO’s report put their findings on the individual mandate in the context of a Laffer curve let alone follow up with an estimate of the massive economic damage that comes with pushing a tax down to point D. It should be no surprise that, in doing the necessary work, the current CEA found massive net benefits of moving from point D to point A even after considering the various benefits of expanding health insurance coverage.

President Trump and Congressional Republicans recognized the historical damage done by the individual mandate well before economists did, even while it is economists who specialize in such matters. President Trump reached the (important and correct) conclusion sooner because he reasons differently on issues like this. Simulated annealing is a close analogy that I’ll write about later. He did not get ahead of us by “playing 3 dimensional chess” or drawing Figure 2: that would be the kind of deductive reasoning that is prevalent in economics and proved slower at reaching the answer. Many critiques of the President assume that deduction is the only method and thereby entirely miss the point of simulated annealing, which is that he would try both criticizing the mandate and (albeit briefly) praising it and then closely monitor the feedback. I suspect that members of Congress did something similar (President Obama also recognized -- just privately until he left office -- that there was more to the individual mandate than the technocrats were telling him).

Health regulation is just one area of Federal policy where some of the most interesting economic history is happening now….

No comments:

Post a Comment